What Drives High Growth Rates, Miracle Economies, and Disasters

The Swiss INSEAD Alumni Association invited Ilian Mihov to speak to alumni and special guests in Zurich in May. We are pleased to publish here an exclusive report about his presentation and the evening’s activity. Professor Mihov is in high demand for his research on emerging markets. He is also now the new Dean of INSEAD, a role that he undertakes with a vision is to keep INSEAD on the vanguard by developing “responsible, thoughtful global leaders who will transform companies, communities and nations throughout the world.”

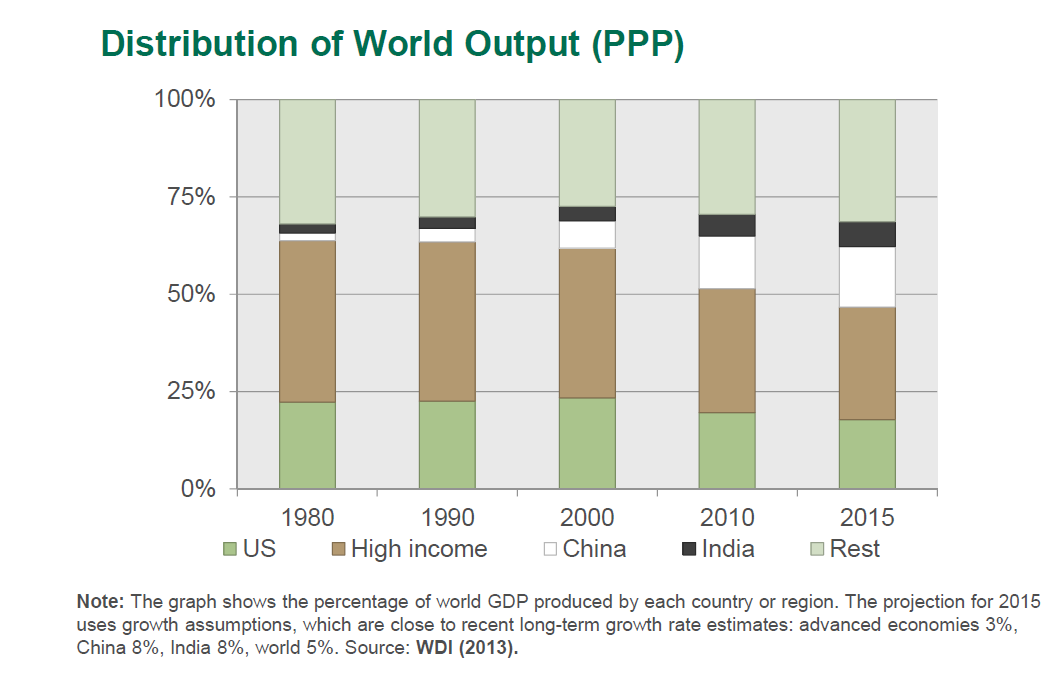

ZURICH Friday, 03 May 2013- This month the Yuan climbed to its strongest level against the US dollar since 1994. India’s Rupee climbed to a two-month high as inflation there eased, and Brazil’s Real is slightly up since the beginning of the year. Do these gains mean that the so-called emerging markets are about to wrest economic power from the US and Western European countries? No, the timeline has not changed, according to Ilian Mihov, INSEAD Professor of Economics, and Interim Dean. The past fifteen years of consistent economic growth in emerging market countries has been unprecedented, particularly in China and Singapore. “But the world’s economic power is currently distributed in favour of the US and European countries, which combined, currently represent close to 50% of global GDP. Change is underway in the long term. In 1980 the richer countries represented 60% of output, but by 2015 it will still be 47%,” said Mihov speaking at a Swiss INSEAD Alumni Association event in Zurich in early May organized by Alexander Wyss, a partner at Baker & McKenzie and President of the Zurich chapter.

ZURICH Friday, 03 May 2013- This month the Yuan climbed to its strongest level against the US dollar since 1994. India’s Rupee climbed to a two-month high as inflation there eased, and Brazil’s Real is slightly up since the beginning of the year. Do these gains mean that the so-called emerging markets are about to wrest economic power from the US and Western European countries? No, the timeline has not changed, according to Ilian Mihov, INSEAD Professor of Economics, and Interim Dean. The past fifteen years of consistent economic growth in emerging market countries has been unprecedented, particularly in China and Singapore. “But the world’s economic power is currently distributed in favour of the US and European countries, which combined, currently represent close to 50% of global GDP. Change is underway in the long term. In 1980 the richer countries represented 60% of output, but by 2015 it will still be 47%,” said Mihov speaking at a Swiss INSEAD Alumni Association event in Zurich in early May organized by Alexander Wyss, a partner at Baker & McKenzie and President of the Zurich chapter.

Redistribution is however inevitable based on current growth rates (See Distribution of World Output graphic). “By the year 2050 the US might represent only 10% of output based on GDP,” said Mihov who said that he has not changed his outlook significantly since 2011.

Redistribution is however inevitable based on current growth rates (See Distribution of World Output graphic). “By the year 2050 the US might represent only 10% of output based on GDP,” said Mihov who said that he has not changed his outlook significantly since 2011.

“There have been slight fluctuations of growth rates in the past couple of years, but the trends remain strong and they determine the long-run evolution of the global economy. The reduction of China’s growth rate was largely expected. When you have one bulldozer, adding another one increases capital and possibly output by 100%, but adding a third only increases capacity by 50%,” quipped Mihov on the side-lines of the alumni event.

Countries like China, Malaysia, and India are growing. Growth is driven by imitating and replicating, a model followed in the sixties and seventies by Japan and now by Korea and other emerging economies. “These drivers are replicating and imitating, and they will be the drivers for some time to come. The key ingredient for this growth is investment and mobilization of the workforce,” said Mihov.

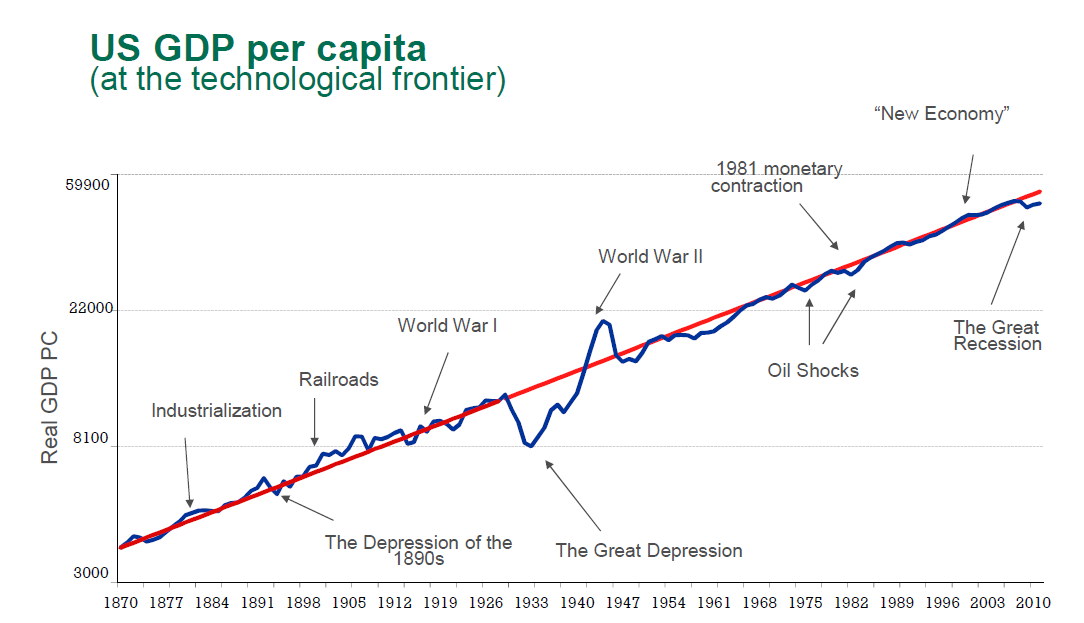

“Rapid growth of 8 to 10% is possible during the catch up phase, but the growth slows once a country converges on the so-called technological frontier established by the US and followed by other countries, such as Japan, Germany, and other G7 countries,” said Mihov, explaining that it makes no sense to invest in innovation at this stage of development.

The Bulgarian-born economist discussed the concept of the technological frontier. (See the red line in the graphic entitled US GDP : at the technological frontier). “Wealthy countries are already at the frontier and cannot grow faster than the rate of the frontier (about 1.85% per annum). “Poorer countries can and will often grow very quickly until they reach the frontier, after which they grow at the same speed as the rich countries,” posited Mihov. He argues that long term growth at the frontier has been surprisingly stable as seen in the US, despite oil shocks, recessions, depressions, and world wars.

He warns of extrapolating growth rat es of emerging economies indefinitely, which can happen if one is not aware of the convergence and frontier concept. He pointed out that several renowned economists once predicted back in the seventies that Japan’s economy, which had a high growth rate due to imitation and replication, would overtake and outpower that of the US. Instead it converged on the more modest 1.85% growth rate along with the advanced economies. “It is the same story for Korea,” he said.

es of emerging economies indefinitely, which can happen if one is not aware of the convergence and frontier concept. He pointed out that several renowned economists once predicted back in the seventies that Japan’s economy, which had a high growth rate due to imitation and replication, would overtake and outpower that of the US. Instead it converged on the more modest 1.85% growth rate along with the advanced economies. “It is the same story for Korea,” he said.

Mihov’s work removes the mystery and gives credible reasons why some countries get rich and others remain poor or become “disasters”, rather than “miracles”. Miracle growth rates are not really miracles nor random. They are the result of a high rate of investment, at least 25% of GDP, plus productivity improvements. In Latin America, Brazil and Chile have had periods of good growth, but also some disappointing periods. For example, Brazil recorded an average growth rate in income per capita of only 0.4% between 1980 and 2005, while during the same period Chile managed to grow rapidly and to become now the richest economy in the region. It is worth noting Argentina was at one time a strong and thriving economic power. It was outpunching Italy, but it has stalled in the last 50 years and today it is still a middle income country.

Mihov said that his studies show that economies become “disasters” or get stalled not because they lack machinery, nor because workers and skills are in short supply, nor because they lack natural resources. It is because some countries cannot or will not improve institutions, reduce corruption, and enact reforms. As an aside, Mihov pointed out that resource-rich countries do not grow as quickly as one would expect. A wealth of natural resources can in fact be a liability. The reason is corruption. He also showed that investment in human capital only without a strong institutional foundation and capital investment program is not a particularly effective way to foster growth. Improved education can accompany negative growth. Why? Brain drain.

Today China and other fast growing economies still score very low on income per capita against the US, Europe and Japan. “It will take quite some time for emerging markets to grow annual income per person from a few thousand dollars to the current level of the US and Europe, which is about $50,000 annual income per capita,” said Mihov. Before reaching parity, each of the poorer countries have to cross what he calls the “great wall”, the point where income per capita is around fourteen thousand dollars. At that point, a country has to navigate carefully; one essential is to make sure the country has good institutions. Political mismanagement can prevent growth from increasing to reach convergence on the technology frontier, according to Mihov. His discovery of the “great wall” was a result of an extensive study co-relating a large number of economic and governance indicators for about 100 countries over an extended timeline.

One of the countries that has exhibited the most miraculous growth over a 35 year period was a surprise: tiny Botswana, a land locked African nation. Mihov said that it had been growing for decades from a very low basis faster than Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong. He says its success was due to a decision to form quality institutions after the British left the country to its independence. After an hour of listening to Mihov’s studies and observing his extensive models it became clear that institutions matter, good governance, including property rights, ease of doing business for entrepreneurs, rule of law, independent central banks, and the ability to reform are all combined to highly influence the potential rate of growth in emerging economies. (Image Source: Ilian Mihov)

On the sidelines

Discussion was lively following the presentation at the historical and elegant Zunfthaus zur Waag near Paradeplatz in Zurich as attendees enjoyed an Apero Riche with wine and soft drinks. Mihov is clearly a well-respected INSEAD lecturer. One alumnus told this reporter that she’d exempted his course when doing her MBA, a mistake she was keen to amend by attending the event. “I am fascinated by him because I’d heard how so much about him and how he challenges students. They are the top, smart, and well-educated, and yet he managed to challenge them to think more deeply,” she said.